a sermon, based on Luke 16.19-31, preached with the people of Epiphany Episcopal Church, Laurens, SC, on the 19th Sunday after Pentecost, September 25, 2016

“If they don’t listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.”

Once again, Jesus speaks sternly; his tongue, no fine rapier slicing neatly, but a bludgeoning sledgehammer assaulting the ear with a hard word difficult to receive, easy to reject.

Yet before we do, running the risk of missing an important message, remember that every teaching of Jesus (as is true of anyone) has a target audience. In this case, the Pharisees, especially those “who were lovers of money.”[1] That love, we are warned, is “a root of all kinds of evil (leading) some to wander away from the faith and pierce themselves with many pains.”[2] That love often afflicts folk with the ills of greed and envy, mistrust and conflict. And sadly do I testify to occasions when I’ve witnessed that love give birth to bitter family rivalries when issues of bequests became the focus, the locus of sorrow!

So, if we believe money is a primary symbol of our human self-worth and, therefore, supremely desired, this parable is for us. If we don’t, it isn’t. Nevertheless, let’s not tune out too soon, for there remains a lesson here for us.

This parable is riven with severe division. Between an unnamed abundantly rich man and poor Lazarus. Between the rich man’s bountiful blindness, not necessarily callousness, but unconsciousness to human need and Lazarus’ painful awareness of his lack. Between this world and the next. Between the earthly gates that divide rich and poor (the ever-widening gap in socioeconomic extremes and the exorbitant financial and moral costs to all of us is one of the most significant issues of our or any time) and the eternal gap that stands, along ethical lines of strict fairness, between the retributive punishment of the formerly wealthy man and the restorative prosperity of the previously poor Lazarus.

As all stories are formed within a historical context, this parable tells us our forebears believed that life’s material blessings were from God, bestowed with the price of their right use in the service of others. That there is an after-life of eternal consciousness when the fortunes of the acquisitive rich and the misfortunes of the poor are resolved, reversed. An ancient theme echoed in Jesus’ teaching, “Many who are first will be last, and the last, first,”[3] immortalized in that Negro spiritual I learned at my Baptist grandmother’s knee, “Rock o’my soul in de bosom of Abraham, Lord, rock o’my soul”, and enshrined in Martin Luther King’s declaration, “the arm of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”[4]

Still, we, in our day and time, must interpret this parable. In our quest for meaning, one classic method is to ask: With what character or characters do we identify?

Those I commend to you who most capture my attention and fire my imagination are not the rich man and Lazarus, for I am neither that wealthy nor poor, but also because they have died and dwell in the fullness of eternity’s torment and blessing. Not Moses and the prophets who represent the sacred scriptures of our Hebrew forebears. Not Abraham whose bosom is the symbol of comfort in Sheol or Hades where the righteous dead await Judgment Day. Not even Jesus, the one raised from the dead. But rather the rich man’s five brothers (in the Greek adelphoi, when translated “siblings”, includes sisters!). As they, like us, are alive and living in this world, we might identify with them.

If we do, we might hear this parable, another of Jesus’ teachings dealing with our possessions and how we use them, as a proverbial “wake-up call.” Like the experience of Ebenezer Scrooge of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (who, at least, did have someone or something, the ghost of Jacob Marley, his former partner, like Scrooge, a miserable misanthropic miser, come back from the dead to warn him!), this parable calls us to see our sisters and brothers in need, whether physical, emotional, or spiritual, and to act to alleviate that need.

If we are generous with ourselves and our substance in the service of others, this parable commends we continue. If we are not, this parable commands we consider it. Now. For like the five siblings, we have our “Moses and the prophets”, our sacred scriptures replete with manifold lessons of God’s love and care for the least, last, and lost. Unlike the five siblings, we have One risen from the dead, Jesus whose life and death of self-sacrificial love is to be resurrected and incarnate in our daily Christian living. Thus we, whilst we have time, have a chance to change.

All of us probably are in between. In some ways, with some folk, at some times, generous. In other ways, with others, at other times, less. Where in your life and mine do we desire to continue our generosity? And where and with whom do we need to increase our liberality?

Photograph (by Walt Calahan): me preaching at The Washington National Cathedral, Friday, January 27, 2006

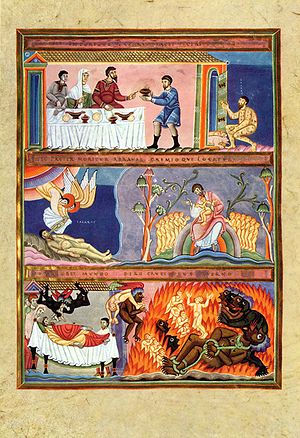

Illustration: Lazarus and Dives from the Codex Aureus of Echternach (11th c illuminated Gospel Book). Top panel: Lazarus at the rich man’s door. Middle panel: Lazarus’ soul carried to Paradise by two angels (left) and Lazarus in Abraham’s bosom (right). Bottom panel: Dives on his death bed (left), Dives’ soul is carried off by two devils to Hell (left, above), Dives tortured in Hades (right). (N.B., Though in the parable the rich man is given no name, by tradition he has been called Dives, which is Latin for “rich.” The name Lazarus is an abbreviation of Eleazar, meaning “God helps.”)

Footnotes:

[1] See Luke 16.14.

[2] 1 Timothy 6.10, paraphrased. 1 Timothy 6.6-19 is the epistle reading appointed for the day.

[3] Mark 10.31

[4] From the speech, Our God Is Marching On!, delivered on March 25, 1965, on the steps of the state capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama, at the conclusion of the civil rights march from Selma.

I so love these sermons Paul where you leave us with questions!! I believe we continue to help those in need when it’s obvious that the need real / legitimate. I have several causes I give to that I know have serious need (some around education) and I’ll continue that for as long as I can.

I’m much less liberal with help for people I’ve helped many times over. I want them to benefit from my help enough to move forward with their lives, not to be relied upon to be their safety net. I think everyone has limits with their generosity and unfortunately there can be problems when that limit is reached….

Spiritually and emotionally I think we should give as much as we can because we never know how many times we’d have to call on someone. I’m more willing to give of my self and my time than I am to give of my funds.

I’m exhausted as I write this because I gave so much of myself to Caregivers this weekend in St. Croix. That said, I received sooooo much from them that i feel that I was the winner in terms of what I gained spiritually and emotionally for my healing. I feel lighter emotionally now than I did just two days ago.

When I feel refreshed as I do now I’m more likely to be liberal with my funds…. I think because I feel fed I want others to feel fed too!

Much love and thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, yes, I can relate to all you write. Verily, your words resonate within me.

As you have given of yourself so fully and freely and faithfully this weekend, you also attest to having been fed. Wonderful, I believe, when the giving and receiving is characterized by mutuality! Still, I pray you take time for rest and recuperation. (Though I know that as soon as you return home you’ll be in the thick of service with US against Alzheimer’s!)

With my deepest live and highest respect

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Paul!! I will promise you that I’ll rest and relax! I’m in my room for the evening after helping the event staff pack up the conference center. I don’t head to the airport til 1pm. So I’ll sleep in and chill by the pool til time for my flight. Thanks for your care of me! Much love!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Travelin’ mercies, dearest sister. Love

LikeLike